In the light of subsequent events, it is amusing to learn that in 1948 the Argentinian football association imported eight British referees to help them raise the standard of officiating. Each was provided with an interpreter, a facility sadly lacking at Wembley 18 years later when the captain of Argentina wanted to communicate with the German referee of the World Cup quarter-final against England in order to establish precisely why he was being sent off.

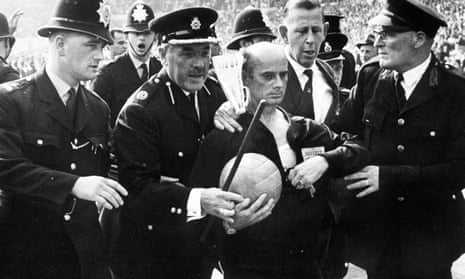

That famous confrontation between Antonio Rattín and Rudolf Kreitlein – which held up the match for several minutes, depriving one team of their charismatic leader while giving their opponents a helping hand towards a moment of destiny – was among the most prominent of several incidents that have shaped the footballing relationship between England and Argentina.

“Rattín was, without question, one of the great moaners of the 60s, forever pleading with referees,” Jonathan Wilson writes in Angels with Dirty Faces, his new history of Argentinian football. “On this occasion he seems to have been relatively restrained.” But those English fans who were watching, either in the stadium or on television, will remember the sense of disbelief that a sportsman could bring a match to a standstill by refusing to accept the rule of authority.

It was the beginning of a long mutual misunderstanding, confirmed in the minds of the average English fan two years later when Manchester United met Estudiantes de la Plata in the two-leg final of the Intercontinental Cup. There had been a warning a year earlier when Celtic faced another Argentinian team, Racing Club, in the same competition.

Ronnie Simpson, the Scottish goalkeeper, was hit by a missile and put out of the second leg in Buenos Aires before it had even started. A bloodbath of a play-off in Montevideo saw six players dismissed, four of them Scots. Bobby Lennox left the pitch only when ordered to do so by a policeman with a drawn sword while Bertie Auld somehow managed to stay on and complete the match, which the South Americans won by the only goal.

In Wilson’s words, Manchester United’s two meetings with Estudiantes “picked up where Racing’s clash with Celtic had left off”. Nobby Stiles was dismissed in Buenos Aires after committing 10 of United’s 17 fouls (against 35 by the Argentinians) during the match, eight of them on Carlos Bilardo, his opposite number, and having suffered a wound from a head-butt as the home team won 1-0. In the second leg George Best and José Hugo Medina were sent off for fighting.

Between an early goal by Juan Ramón Verón – father of Juan Sebastián, later to play for both clubs – and the unavailing late equaliser by Willie Morgan, many other brutalities went unpunished. Estudiantes’ attempt at a lap of honour was thwarted when objects rained down from the Old Trafford terraces.

Ten years later there was a truce when Osvaldo Ardiles and Ricardo Villa, two members of the squad who had just won the World Cup on home ground, arrived in London. Tempted by Keith Burkinshaw to join Tottenham Hotspur, they proved an adornment to the English game and are fondly remembered. The tragic absurdity of the Falklands war in 1982 prompted Ardiles to take a judicious sabbatical with Paris Saint-Germain, but he returned once the hostilities were over and his farewell match in front of a full house at White Hart Lane, on the eve of the 1986 World Cup, was distinguished by the presence of Diego Maradona, whose partnership with Glenn Hoddle – giving up his No 10 shirt for the night – against Internazionale was a joy to behold.

Within a month, however, Maradona would be raising his hand above Peter Shilton to score a goal that reopened all the old wounds. To one side it represented a gleeful revenge for a hoard of slights going back way beyond the Falklands to the looting of Buenos Aires in 1806 by British warships under the command of Sir Home Popham. To the other it reinforced a belief that all South Americans were, essentially, cheats. The contretemps between Diego Simeone and David Beckham in Saint-Étienne in 1998 seemed just one more example of an eternal conflict between Argentinian wiles and English naivety.

Wilson, as you would expect from the author of several important books on football history and tactics, goes far deeper than the stereotype. In terms of fine-grained and often original research, he is the football writer most likely to tell you that, back in 1905, River Plate’s first-ever opponents included a man who would go on to win a Nobel prize for discovering the role of pituitary hormones in regulating blood sugar in mammals. Equally, however, as a writer who knows and appreciates Argentina, he is prepared to take on the more demanding task of telling the story in parallel with that of the country’s turbulent political and social evolution.

Against the constant rat‑tat‑tat of coups, counter-coups and assassinations, through the eras of Eva Perón’s descamisados and General Videla’s desaparecidos, football provided a sense of continuity, but it could not avoid being tainted by the violence and corruption of the society in which it grew. A wilful insularity, emphasised when Juan Perón kept them out of the World Cups of 1950 and 1954 in order to avoid the risk of demoralising failure, leads Wilson to this intriguing conclusion: “Essentially Argentinian football grew in isolation, without natural predators, which led to the development of an idiosyncratic but vulnerable style of play, one based on individual technique and attacking, and followed with a devotion that arguably no country has matched before or since.”

Periods of economic chaos forced players to accept offers from abroad, wreaking devastation on the always chaotically administered domestic game. When England met Argentina in Sapporo in the 2002 World Cup, British journalists swapped players’ quotes with their South American counterparts, as is customary; this time, however, we broke the usual quid-pro-quo custom by giving them money, because back home the peso had crashed, the banks were boarded up and they were suddenly penniless.

Mostly, though, in his densely detailed but absorbing book, Wilson reminds us of the better things: those we can only regret having missed, like the five-man River Plate forward line of the 1940s, known as La Máquina, and their equally devastating successors of the 50s, whose popular nickname gives his book its title, and those, from Ardiles to Agüero, we may have been lucky enough to witness at first hand, all the beautiful fruit of a bittersweet history.

Angels with Dirty Faces is published by Orion on 11 August. Available at bookshop.theguardian.com