At a press conference held in a Valencia hotel two weeks ago, Jesús “Suso” García Pitarch was asked why Peter Lim had bought the city’s football team in the first place. It was a loaded question, one supporters have pondered often over the last couple of years, and the answer, or the lack of one, felt loaded as well. Pitarch, the sporting director recently back from Singapore where he had met with the owner to discuss plans for the club only to resign soon after, replied that he had never asked and had no explanation either. “I don’t know,” he said. “I suppose he likes football.”

The son of a Singaporean fishmonger who had previously made a bid for Liverpool, a business partner of the Class of 92, with investments in Salford City FC and Manchester’s Hotel Football, as well as in Formula One, Lim took over at Valencia in June 2014 with an initial €94m (£81m) investment. In a deal brokered by the then president Amadeo Salvo and the agent Jorge Mendes, Lim paid €22m up front, and loaned the club a further €72m for a 70% share, later taking that above 80%, with his total outlay so far close to €200m.

Valencia were in crisis, a club with two stadiums – one they could not sell and one that they could not afford to finish building – and a debt of €230m, the repayment of which was restructured. The risk of going out of business was very real, they had suffered disastrous presidents, routinely lost their best players, and were effectively owned by a bailed-out bank, so Lim was welcomed as their saviour. In his first season, with players brought to the club paid for and owned by his company, Valencia returned to the Champions League under their new manager, Nuno Espírito Santo. A sense of momentum developed, a communion between fans and club, but it did not last.

There were chants of “Lim, we love you”, but it’s different now. Before the first game after Christmas, some supporters gathered outside Mestalla, holding a banner that declared: “Lim, go home.” Inside, there were further chants: “Peter, go now!” That was repeated last weekend. The sentiment was clear, even if there was something that jarred a little about the chants, something that would have been pointed, too, had it been deliberate: Lim was already home, not there.

“I’m just speculating”, Pitarch insisted when he suggested that Lim “likes football”. He has not been to watch Valencia – his team – for over a year. The closest he has been was in the summer when he was up the coast in Barcelona, arranging the sale of Paco Alcácer – the striker they had said was not for sale. “What sensibility does that show towards the fans?” Pitarch asked, more than a little self-interestedly.

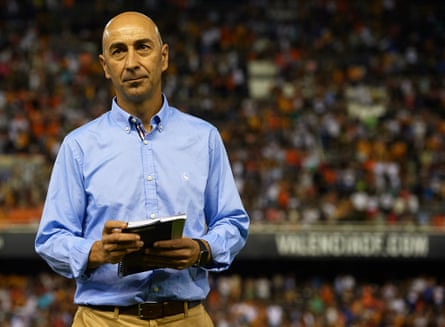

Photograph: Manuel Queimadelos Alonso/Getty Images

Whatever Lim bought Valencia for, it wasn’t for this. To own a club failing on the pitch and struggling off it, still with two stadiums, still in debt, apparently engulfed in continuous crisis, where the captain Enzo Pérez says they have hit “rock bottom” only to be proven wrong when things get worse, as they have done steadily for a year; where the team with the fourth biggest budget in Spain stands a solitary place above relegation; where there are divisions in the dressing room; where the fans have turned and the coach and sporting director have turned away, firing shots as they go, prompting the club to fire back, the mutual suspicion and distrust laid bare in public, wounds open. “I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy,” says the club’s former player Mario Kempes.

Pitarch was speaking to the media as he sought to justify his failure and his resignation as Valencia’s sporting director – just under a year since he took the job and 10 days after he claimed to have offered his resignation only to insist that he wasn’t about to “abandon” the club. Staying was about “responsibility”, he said then; now he admitted that he had made “mistakes” over the last 12 months, but that the biggest of all was not walking sooner. “I can’t defend what I do not believe in,” he said, describing the club as being immersed in a “grave institutional crisis.” And so he had gone.

He is not the only one. Pitarch went just days after the coach, Cesare Prandelli. A little before Christmas, Prandelli had held a press conference in which he had declined to answer questions and instead delivered a speech one minute 57 seconds long in which he accused his players of being unprofessional. Speaking in Italian, as he had done since he had taken over, gesturing to the door, he repeated one word over and over: “fuori!” Out! He wanted players who gave their all for the shirt, who “suffered” for it, who “loved” it. Anyone who didn’t could get out.

Fans agreed: one poll showed 98% thought he was right. The club hierarchy agreed too, or appeared to: after the next game, Prandelli travelled to Singapore with Pitarch and the club’s president, Layhoon Chan, to meet Lim. They were on the fringes of the relegation zone and reinforcements were top of the agenda, so were departures. Prandelli was given reassurances, or said that he was, but the economic reality was inescapable and shifting players out is not as easy as it sounds. Others asked recurring questions, like what the real motivation was? Was football the only factor? Why were the signings made and why have they failed?

In the summer, Valencia had raised over €100m, their best players departing – André Gomes, Alcácer, Shkodran Mustafi – while those they had wanted to sell stayed. The winter would not remedy that entirely, and Layhoon Chan publicly warned it was not just a case of Lim reaching into his pockets. Financial fair play – talked about as if it is somehow nothing to do with the way the club is run, an imposition upon their work rather than a consequence of the way they work – meant that they could not spend what they do not generate. Valencia do not even have a shirt sponsor.

Lacking faith, Prandelli resigned. He had claimed to do so, in part, because Simone Zaza, the striker he wanted, wasn’t coming, but Zaza has come now. He had gone precipitously and emotionally, doing his own credibility little good, but he had not done so entirely surprisingly. The window had not opened yet, but he said Valencia wasn’t run by “football people.” They accused him of seeking excuses, running away from his own inability to rectify results. He had been there 90 days.

Pitarch had promised to resign with Prandelli but reneged; 10 days later he actually did, departing a disaster. Pitarch was the third sporting director of the Lim era: Rufete had been sacked in a power struggle in the summer of 2015; his replacement Nuno, the coach who became manager as well, was soon unpopular with fans and was sacked in November 2015. Pitarch took over in January 2016 and was gone in January 2017, resigning just as the transfer window opens, leaving the head of the youth academy, Alexanco, to take over in a hurry, diving straight into the market.

As for Prandelli, he was the seventh coach of the Lim era. Pizzi had been sacked just before the takeover on Lim’s behalf; Nuno was sacked in November 2015; he was momentarily replaced by Phil Neville and Salvador González “Voro”, a former player, the club’s matchday delegate and their eternal, go-to caretaker boss; next came Gary Neville, Lim’s business partner; Gary Neville was sacked in March and replaced by his assistant, Pako Ayestarán, who was in turn sacked in September. One after the other, each worse than the last: under Nuno they won 49% of the points; under Gary Neville, 29%; under Ayestarán, 27%; under Prandelli, 25%.

The season was only five games in, and it was only three months since he had been given a new contract, when Ayestarán was sacked. Pitarch publicly announced that he wouldn’t have kept him on at all, only there had been no money to get a replacement. It is remarkable how little was made of that comment at the time. Voro briefly took over again and when he left again to make way for Prandelli – who had been found and flown round the world to meet Lim – he said he hoped “never” to be there again. Now, though, he is back for his fifth spell in charge, his third in two seasons. This time, for the first time, he has been given backing. Well, sort of: he will be in charge until the end of the season and his contract is a managerial one for the first time.

The task before him is a big one, but it is a familiar one too. “Either we show our bollocks, or we’re going to shit,” the forward Santi Mina said after one loss recently. Valencia, the fourth biggest club in Spain, have made their worst ever start to a season and are just four points above the relegation zone. The good news amidst the bad news is that the departures of Prandelli and Pitarch, the conflict that their exits brought to the surface, may prove cathartic, some clarity achieved; the restructure should be beneficial. And then there’s the fact that there’s something about Voro.

They’ve nicknamed Voro “Mr Wolf”, Valencia’s temporary solutions man, the person you call when there’s a crisis, a mess to clear up. The coach who is not a coach has the best points record of any coach in the club’s history; this season he has led Valencia to 10 out of a possible 15 points, compared to none out of 12 for Ayestarán and six out of 24 for Prandelli. The latest of those came this weekend, in his first league game back. Valencia won, beating Espanyol 2-1. They needed to, things have got that bad; the club that considered Champions League qualification as standard now have another, less ambitious target. “The objective is to avoid relegation,” Voro said, “and I am convinced we can.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion