Just like thousands of other Liverpool supporters, I set off for Sheffield on the morning of 15 April 1989 with that giddy mixture of excitement, anticipation and anxiety that accompanies an FA Cup semi-final. I’d been to four FA Cup finals by then, sampling two wins and two defeats. And I’d been there, too, when Liverpool were knocked out of the Cup at the semi-final stage in 1979, 1980 and 1985. If the Cup final defeats were hard to bear, it was tougher still falling at the penultimate hurdle. There’s no pain quite like a semi-final knockout blow – or so I thought.

There were four of us in the car. Hobo – Ian Hodrien – was driving, with myself and my brother Neil in the back. Our special guest was a Juventus supporter, Mauro Garino, a mate we’d first met in Dover when he was hitching back from Celtic in 1981. Mauro had been coming to Liverpool every year since then, usually staying at ours over Christmas. Our friendship had survived the Heysel Stadium tragedy in 1985, and Mauro’s one big ambition was to watch Liverpool in an FA Cup final at Wembley. It was his birthday on 8 April and I got him a ticket for the next best thing – a semi-final between Liverpool and one of the best teams of the country, Nottingham Forest.

We headed off that fine spring morning with hope in our hearts, yet hopelessly unaware of a series of unrelated events that were already combining to disastrous effect. One such factor was a major hold-up between Hyde and Glossop, where roadworks slowed traffic to a standstill.

Eventually, we got through the Glossop bottleneck and headed over the sun-dappled Snake Pass, taking the Rivelin Road shortcut into north Sheffield. I had been to Sheffield Wednesday many times before and, from my days as a student in Sheffield, I knew the Hillsborough area well. I convinced everyone that we’d get served quicker if we avoided the popular pubs near the ground and went to the Freemasons Arms, a famous old pub in the back streets of Hillsborough itself.

So we parked up a fair old walk from the ground, and headed into the Freemasons around 1.30pm. So much for my plan, though – it was packed, with as many fans from Nottingham as Liverpool thronging the bar. The atmosphere was brilliant, everyone happy in spite of the prolonged wait to get served. Mauro tried to start his ‘song of scarf ’ – a version of ‘You’ll Never Walk Alone’ that, inevitably, consisted of him wailing various syllables – and was only mildly bemused when the Forest fans drowned him out with, “What the fucking hell was that?” It was the last time we’d be laughing that day.

The pub started to empty out. I was agitating for us four to take advantage of the sudden lull so we could squeeze in one more pint, assuring the others I knew of a shortcut to the ground. Neil and Hobo were wise to my shortcuts, however. They checked with the bar staff, who confirmed that the football ground was a brisk 15-minute walk away, so that was that. At 2.15 p.m. we made our way towards the ground. Yet, as we got closer, it became apparent that the way ahead was completely blocked. There was a backlog of Liverpool supporters, 10 or 12 abreast, queuing up but, seemingly, going nowhere.

This is no revisionist hindsight – the crowd was, in the main, good-humoured. I went across to ask a policeman what was going on; why the crowd wasn’t moving. The only reply I received was, ‘What’s up with you? Are you nesh?’ I think he was saying that a certain amount of pushing and shoving was only to be expected at such a big game, and I should tough it out.

Lord Justice Taylor’s Interim Report of August 1989 says that Chief Superintendent Duckenfield’s second-in-command, Superintendent Bernard Murray, received a message from his commander on the ground, Chief Inspector Creaser, at around noon. Creaser asked Murray whether the Leppings Lane pens should be opened, and filled, one at a time. Murray’s reply illustrates a blind faith in what was, effectively, self-policing among football crowds. He said that all pens should be opened simultaneously, as fans would ‘find their own level’. That kind of thinking might have some plausibility in a huge, unsegregated end like the Kop but, with Leppings Lane sectioned off into pens by radial fencing, it was a huge risk assuming we would simply work things out among ourselves.

The problem that faced us was that there were only seven turnstiles servicing that route into the ground. Yet many of the 10,000 Leppings Lane ticketholders, as well as the 4,500 with seats in the West Stand above it, would all be gravitating towards those solitary seven turnstiles. And, on the day, it was even worse: because of the way the police were segregating fans, they blocked off access to the main road feeding the remaining 16 turnstiles on the other side of Leppings Lane. This meant there were also North Stand ticketholders compelled to enter the ground via the same besieged turnstiles. It was turning into a free-for-all, and I was, by now, very glad that we hadn’t stayed for that third pint.

With hindsight, the lack of turnstiles, added to the physical restrictions of the area outside the ground, are the main reasons for the insufferable build-up before the game. In simple terms, the geography of Leppings Lane dictated that there was no overspill, nowhere for the ever-growing crowd to go. But there are other factors, too. There was absolutely no leadership or direction from either the police or the Sheffield Wednesday stewards.

As more and more people tried to fit into the narrow confines outside the turnstiles, I found myself being propelled, feet off the floor, closer and closer towards a red-brick wall. I was powerless to change my direction, or the angle at which I was being carried. My face was being pushed into the wall, when my brother, Neil, arrived behind me. He forced the palms of his hands flat against the wall, either side of my head, and used the leverage to push back, creating a little space for me to manœuvre in. At that exact moment, the concertina gate to our left opened. We stood back for a second expecting the police to eject someone, or police horses to come in or out. Then, slowly, people started to file in. Neil and I went through, and waited for Mauro and Hobo.

We stood to one side on the concourse, just inside the gates, where people were buying refreshments and matchday programmes. The concourse area was small, almost diamond-shaped, and would have seemed crowded with just a few hundred people standing around. But with the steady flow of fans now coming in three, four or five abreast, sight-lines to the limited signage directing supporters to alternative entrances were almost completely obstructed by the ever-growing number of fans on the concourse.

Only one sign could be clearly seen. Directly above your head as you came through the turnstiles was the tunnel that led to the central pens, 3 and 4. It was unmissable, one big sign directly above the tunnel with the word STANDING.

The tunnel shelved down to a steep, 1:6 gradient. Such tunnels in city centres, train stations and pedestrianised areas are typically flat, with 1:10 the accepted norm for a safe, gently sloping tunnel. But at Hillsborough, at peak, pre-match capacity, many fans would be swept down the steep Leppings Lane tunnel towards whichever pen the flow might take them.

The Leppings Lane terrace had been divided into six sections, each closed off with radial fencing – pens, essentially – of which numbers 3 and 4 were situated directly behind the goal. The terrace was just about fit for accommodating a small-to-average 1980s away support. But for a major occasion like the FA Cup semi-final, the turnstiles, the concourse and the terracing itself at the Leppings Lane end were all woefully ill-equipped.

And Leppings Lane had already experienced a history of crowd problems, and especially in the FA Cup. At the 1981 semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Tottenham Hotspur, Spurs fans experienced unbearable crushing on these same terraces. On that occasion the South Yorkshire police responded quickly to the danger and opened gates in the fencing to allow Spurs fans to spill out on to the pitch. After the problems at that game, Hillsborough was not used again as a semi-final venue until 1987, when Leeds United played Coventry City. But the lessons of 1981 had not been learned. There was, once again, overcrowding in the central pens, and Leeds fans in the seats above had to haul crushed and fainting fans to safety.

We spotted Mauro and Hobo heading for the tunnel. I managed to grab Hobo’s jumper, pulling him back and shouting “Mauro” at the same time: “This way!”. To this day, I cannot contemplate what might have happened had I not known the ground’s layout as I did. Perhaps if I hadn’t been so slight I’d have taken my chances with the majority. But my instinct was to head away from the numbers and find a quieter ‘spec’. Even as we made our way to the corner passageway, carnage was already unfolding on the Leppings Lane terracing.

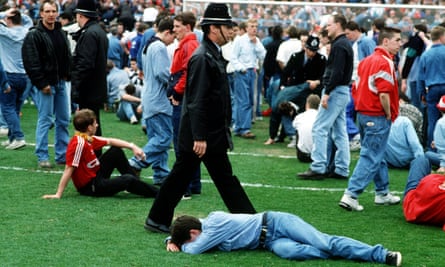

What happened next has come to be known as ‘the Hillsborough tragedy’. Yet the word ‘tragedy’ implies something accidental. But Hillsborough was far from being a tragic accident; it was a man-made disaster. There were warning signs and opportunities in the build-up to the game, and on the day itself, to avert the inevitable. These indicators and options were ignored, leading 96 to their deaths. So our sadness for that tragedy should be matched by our righteous anger at its causes.

Hillsborough Voices by Kevin Sampson is published by Penguin Random House. The paperback version is released on Thursday, 9 February.