A major discovery in women’s football history has revealed Britain’s first black female footballer – and she was playing in one of the sport’s earliest recorded games in the 1890s.

The emergence of her story is timely. On Tuesday evening, as football’s black achievers gather to be honoured at the Football Black List celebration, Futures Theatre will play out the story of the game’s female pioneers in a new production called Offside. It is the first time the central character of a black female footballer has been dramatised.

If it was not for Stuart Gibbs, an artist with an interest in women’s football, the story might never have been uncovered. While he was researching the history of the women’s game for an exhibition, he found an article in the Stirling Sentinel in June 1896 referring to “a coloured lady of Dutch build” in goal. It took Gibbs a while to find a teamsheet but, when he did, the goalkeeper’s name was Carrie Boustead. Here she was, Britain’s first black female footballer. Or so he thought.

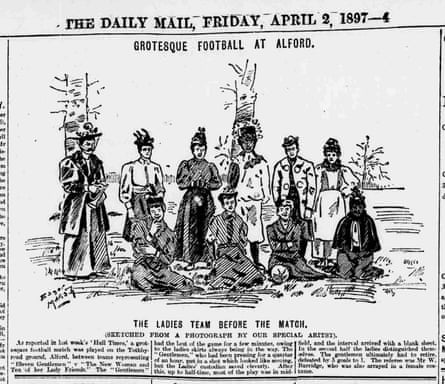

For seven months this pioneer went under that name. But when a colleague discovered a photograph of the team, Gibbs realised he had made a mistake. Boustead was not black; she was white. The name he was searching for was Emma Clarke, who had occasionally appeared in goal but was more usually an outfield player, “the fleet footed dark girl on the right wing”, as the South Wales Daily News put it. Later Emma’s younger sister, Jane, also appeared for the team, and Gibbs thinks there may have been a third sister, Mary.

Not much biographical detail is known about the Clarke sisters. Emma was born in Liverpool in 1876 to William and Wilhelmina Clarke, and began working as a confectioner’s apprentice aged 15. William worked on the barges and the sisters likely played football in the streets – indeed the famous Mrs Graham (real name Helen Graham Matthews) lived just a few streets away from where the Clarke sisters grew up in Bootle. Emma made her British Ladies team debut in 1895, in London’s Crouch End, and both sisters went on to join Mrs Graham’s XI tour of Scotland the following year. Gibbs has traced their playing days as far as 1903 and thinks the Clarkes would have earned around a shilling a week each playing football – plus food and lodgings – a decent amount for a working-class family of that time. Interest in women playing was high and thousands of spectators attended matches, prompting widespread press coverage, though sadly there are no known interviews with Emma.

But the coming to light of her existence is a big moment for the game. While pioneers such as Arthur Wharton, the first black professional footballer, or Walter Tull, have been celebrated in recent years, hardly anyone has heard of the Clarkes. Gibbs is pleased to have sorted out any confusion. “I thought: ‘My goodness,’ then I realised I’d made a mistake and my heart sank. It was good to eventually get it right.” If you look online, however, the case of mistaken identity lingers and Boustead continues to be written about as the first black female footballer.

When Futures Theatre came to the subject – the director, Caroline Bryant, was inspired by her own daughter’s experiences of inequality in the game – they picked up on the Boustead story and wove it into their narrative. For Sabrina Mahfouz, who co-wrote the production with the poet Hollie McNish, the very fact that such an important pioneer could be forgotten, and mistaken, says everything about the under-representation of women, and in particular women of colour.

“I also think it is really important to constantly remind people that there was immigration to this country from thousands of years ago, and that those people had always been involved in the things that are now known as ‘British’.

“The fact that there’s so little to be found about it is part and parcel of the lack of documentation over the years to do with anything outside of the white, male experience. You’d never get that for male footballers,” adds Mahfouz. She has already got a solution: “Let’s set up a Wikipedia page for Emma Clarke.”

As Offside is performed in London a major celebration of black achievement in the football industry will be taking place. For almost a decade the Football Black List has been an important tool in championing and unearthing black talent in the sector. This year the list, newly supported by the Premier League, contains more women than ever – eight out of 30 overall. While individual names such as the Fifa secretary general, Fatma Samoura, and FA board member Heather Rabbatts hold influential positions, black women remain under-represented overall, for example in sports media where BAME women made up only 1.3% of personnel covering the major sports tournaments last summer.

Marcia Willis Stewart, a leading civil rights lawyer at Birnberg Peirce who represented 77 of the 96 families at the Hillsborough inquest, is a powerful addition to the list. Stewart is an Arsenal fan and grew up in a time when “black households were often quite frightened to go anywhere near football crowds”. The lawyer, British-born of Jamaican parentage, represented the families of Jean Charles de Menezes and Mark Duggan, both shot dead by police, but she says she was surprised to receive the award.

“I nearly fell off my chair,” she says, laughing. “I’ve been a human rights lawyer for years but I’ve always shied away from the public arena. But after Hillsborough I realised I had to be more visible because many young people won’t know that you’re out there. They need to see you and we need to see them. So I’ve been reminded that that’s part of my mission to seek them out.” She is touched by the story of the Clarke sisters and reflects on its significance. “Our own ‘Hidden Figures’ are emerging, aren’t they?” she says. “That’s really quite important.”

The England and Arsenal forward Danielle Carter hopes to become one of football’s influencers. Only 23 years old, Carter last week passed her corporate governance course where she studied alongside the former Manchester United forward Quinton Fortune and Hope Powell, the former manager of the England women’s team.

night, instead of attending the Black List celebration, Carter will be shadowing a disciplinary board with the Hertfordshire FA. Talk about dedication. Carter says she is aiming for a place on the board of a top men’s club and along the way would like to contribute to women’s football. “I realise no one’s going to pay me any mind as of yet because I’m young, I have to build up my credibility. This course has opened my eyes to what goes on beyond the managers, outside of the changing rooms. I’d like to get my voice across for people who can’t.”

Next month she is meeting Rimla Akhtar, FA councillor and chair of the Muslim Women’s Sports Foundation, to discuss the representation of ethnic minority women in sport. “Unfortunately discrimination is part and parcel of the world. I’ll be happy to learn on the job and overcome situations – and in years to come put an end to it. I don’t mind taking the brunt of it so that others won’t have to. I bring a different perspective, I’m young, female, black. It will be interesting for the typical white, male, 60-plus category to get a bit of freshness in perspective. Female empowerment matters, football is still very much a male-dominated industry.”

In Offside, the contemporary characters are inspired and strengthened by the stories of the pioneers from the 1890s. In 2017 these new and emerging figures are certain to inspire generations of football women to come.

Offside is on tour to 29 April, full list of dates at futurestheatre.co.uk

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion