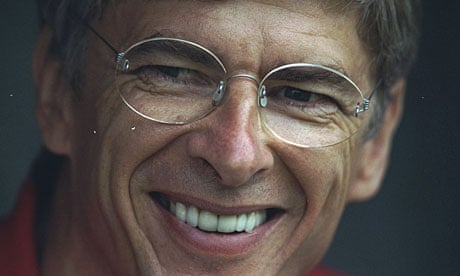

Something important seems to be happening at Arsenal and, like everything else there, it seems to be happening around the towering centrepiece of the manager, Arsène Wenger. Wenger has been emitting puffs of cautionary smoke for some time now and fresh tremors appeared again this week after the unfortunate – but also strangely unsurprising – Champions League defeat by the Portuguese third‑raters Braga.

There was a sharpness to reports of Wenger's testiness afterwards. Among some Arsenal fans there is even the same sense of bunched and tearful frustration you might feel with an increasingly stubborn and militant aged parent who inexplicably refuses to understand about the internet or mobile phones or to be twinkly and unflappable and discreet like the aged parents in daytime TV adverts for low-interest loans that can consolidate all your debts into one low monthly payment. The phrase "lost the plot" has even been cautiously trotted out. So far we have danced around this, but I might as well be the first to say it openly. There seems to be a feeling abroad that Wenger may have gone – or may be on the verge of going – a bit mad.

This must be introduced with the obvious caveat that all football managers need a bit of madness in them. After his retirement as Liverpool manager, Bill Shankly would leave his matchday seat in the stands 10 minutes early and take up a raised position near one of the empty stairwells, perhaps on a ledge or a set of railings, in order to declaim and wave and gesture in pious fashion more effectively when everybody else came filing out. This was considered entirely normal. Alf Ramsey celebrated Ipswich's league title by sitting in furrowed silence until everybody else had left and then performing a solo late-night air-punching lap of honour around a darkened Portman Road. Don Howe would train Arsenal's 1971 Double winners by repeatedly shouting the word "Explode!" at them while they ran up the steps of the Highbury stands – and yet he remains a porkpie-hatted emblem of sobriety.

These days it isn't so much managing that brings out the madness. It is going on television. Roy Hodgson was once notable for his air of calm. Greater exposure at Liverpool has left him looking strangely wild-eyed and haunted, prone to leaping about wearing an oversized padded sports coat with teeth clenched and hair flapping, like some habitually-imploding rogue 1970s detective in a Granada TV series called Roy's Game or Hodgson!

Every manager reacts to these pressures differently. Before this season Ian Holloway would often pretend to be mad for tactical reasons, an affectation that has now dissolved into something more rabidly convincing. At Wolves Mick McCarthy flaunts a certain telegenic madness, affecting the thrillingly windblown hairstyle of a quixotic New York tug-boat captain.

It is different with Wenger. There has always been a suspicion, even during his early flush of success, that madness would one day claim him, that this would be his flaw. It is partly a physical thing. Wenger has peculiarly long arms and legs. Aloof in his touchline rectangle, cloaked in his floor-length quilted gown, he seems to be always on the verge of some burst of frighteningly angular expressiveness. There is also a sense that we have never quite forgiven him for turning up and making us all look so dim and retrograde all those years back, parading his oversized spectacles, inventing pasta, and suggesting a single glass of sparkling mineral water as an alternative form of recreation to leaping up and down in a lager-fuelled circle inside a wine bar called Facez.

The thing about Wenger's low-level madness is that it is very specific. This is the madness of the ascetic and the idealist, one that narrows with age. Wenger has only one way, interpreting all he sees through the prism of frictionless, nimble-footed, free-market Euro-Wengerball. Life has become very simple. If his team loses this is now due to some imperfection in the footballing universe, a failing in his opposition or in the game's administrators that has allowed this ideological catastrophe to occur. Such all-consuming zeal can be deeply seductive. There is a sense that his opinions on everything – on whimsical west coast acoustic coffee shop music, or supermarket own-brand yoghurts – will all be robustly, even angrily infused with this galvanising belief in supra-national sideways-pinging soft-shoe spreadsheet football.

There is a beauty, as well as robust economic good sense, in his absolute one-note convictions. Wenger has gambled all on being right, on refusing, for example, to spend jarring sums of money on an essentially unexciting, non-shirtsleeved, unspiky-haired goalkeeper with a tedious expertise in catching footballs. He remains convinced that the world will ultimately bend his way. And perhaps it already has a little. Wenger will take the journey into the promised new world of Fifa fair-play rules and revenue-based austerity with an ideology in hand and a set of self-drawn maps. He may or may not be allowed to get madder from here. But for the mad-curious neutral it would fascinating if he could be proved right just one more time.