There was something striking about the cheat notes an English player smuggled into a Spanish press room and sneaked under the desk, ready to recite when the moment was right. "And how," he had asked as he copied out the phrases the day before, "do you say that?" The answer was simple: exactly as it's written. One of the beauties of Spanish is that it is largely phonetic. This is not a country that makes spelling mistakes, except for one: Bs and Vs sound virtually identical, ending up erroneously exchanged. Some things become indistinguishable – like voting (votar) and bouncing (botar).

Or Xavi and Xabi.

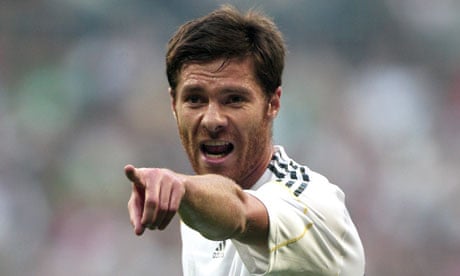

Xavi and Xabi, Xabi and Xavi. Xavi Hernández and Xabi Alonso. They are the X-men currently in the midst of their side's midfields and in the thick of an epic in four chapters – a saga in which Barcelona have been left as virtual league champions and Madrid as actual Copa del Rey winners, in which the trophy that matters most, the climax, will be decided over the next 10 days.

"Indistinguishable" might be pushing it. Not least because Catalan and Basque roots mean that those with sharp hearing can tell the pair apart – not because of the V or the B but because of the X, from a "ch" sound for Xavi to "sh" for Xabi. And because there are differences to their games: Xabi is taller, more imposing, his position is a little more static, a little deeper; Xavi provides the final pass more often, Spain's most important assist provider last season. Xabi's passes travel further; Xavi's travel faster.

Yet there is a striking mutual respect between them and a similarity that, for all the focus on Cristiano Ronaldo and Leo Messi, may make of them the central actors in the drama about to unfold. One that means that it just feels right that they play together for Spain. These are the men who will face each other in the heart of midfield, the men entrusted with bringing an identity to their teams, whose job it is not just to play better but make others play better too.

Xavi is Barcelona's ideologue – bright, opinionated and analytical, the man Pep Guardiola told: "I can't imagine Barça without you." Xabi is one of the few players to discuss tactics with José Mourinho, to contradict him and suggest other approaches, a leader within the Madrid dressing room – intelligent, communicative, quietly authoritative, bringing calm to a team that plays at breakneck speed. These are Madrid and Barcelona's cerebros: their brains.

Real football people, insightful and passionate about the game, in awe at the passion it provokes and absolutely assured as to the way it can be played, they are team-mates and fellow travellers for Spain. And for all the differences between the clubs, for all that Guardiola and Mourinho have divergent approaches, for all that their identities diverged further over the past week than they ever have before, there is an inescapable similarity between them.

Just ask the men who have faced them. When Almería played Barcelona last season, their then coach, Hugo Sánchez, ordered one of his players to man-mark Xavi, cutting off Barcelona's football "at source". When Almería drew with Madrid earlier this season, their then coach, José Luis Oltra, was most concerned with stopping Xabi. "We had to make sure Alonso had as little of the ball as possible," Oltra said. "He is the Madrid player who most makes sense of the game – he plays the best long passes, the best final pass and the controls the game best. There is a real criteria to the way he plays."

Only two Madrid players have won possession back more times than Alonso, but it is that passing, the control, that has been judged to have most defined him here. Just as it is with Xavi.

Guardiola rests Xavi only when he must. Mourinho has avoided rotations this season but when big games come it is Alonso he seeks to protect first. Apart from the 5-0 defeat to Barcelona in November, Madrid have been beaten just twice – by Osasuna and Sporting. Alonso did not start either game. He was missing last year, too, when Madrid were knocked out of the Champions League by Lyon. Liverpool fans who witnessed their side's collapse after Alonso's departure will be familiar with the feeling.

"It turned out that Madrid could play without Cristiano Ronaldo," wrote one columnist, "but they couldn't play without Alonso." As for Xavi, the thought of his retirement has fans of Spain and Barcelona breaking into a cold sweat. They play as they do because he makes them.

Although he identifies most closely with the city of San Sebastián, Xabi Alonso's father, Periko, played for Barcelona for three years and played for Sabadell, meaning that Xabi lived in the Catalan capital for six years, near the city's Avenida Diagonal. So maybe there is a natural affinity, born of experience and location. There is a certain a complicity of criteria and approach, as well as a mutual appreciation.

Friends recall Alonso returning to Liverpool from the Spain squad, stunned by what he had seen Xavi do. But do not take their word for it. Alonso describes Xavi as the player who "probably has the best passing ratio in history if you look at possession, participation and how rarely he loses the ball." "When you are in the middle of a Barcelona rondo [keep the ball]," he told Público, "you feel impotent. You need to know when to put your foot in or else, pum-pum-pum and they get away from you. Xavi loses so, so few. I am lucky to have enjoyed that with the Spanish national team. But when I am with Madrid, I suffer it." He added: "In fact, that was the worst experience of my footballing life."

The lack of control hurts. Much like his counterpart, control is what Alonso is there to provide. While Xavi Hernández has completed more passes than anyone else in Spain this season, 2,794 – 400 more than anyone else – Xabi Alonso has completed 1,558 (before Saturday's games). That is more than anyone in the Madrid side, by a huge difference. He is the only Madrid player in the top 10 and just two non-Barcelona players are ahead of him: Verdú from Espanyol and Villarreal's Bruno. Perhaps, then, it is little surprise that, asked which Madrid player he would steal ready for this series of clásicos, Xavi replied: "Xabi." "Xabi," Xavi said, "is the player that could best adapt to our associative game. He has enormous talent, he is very quick in his use of the ball and very intelligent."

Last Saturday in La Liga, you might have begged to differ; on Wednesday night in the Copa del Rey final even more so. Alonso's game appeared altered. He played long and direct, rarely choosing his passes with characteristic care and reaching half-time with the kind of statistics that screamed at you, so unusual were they. He had completed fewer passes than Víctor Valdés. By the full-time whistle, with the score at 1-1, he had completed just 16. Xavi, in contrast, had clocked up well over one hundred.

That was a fact most noted in the Barcelona camp – and with a quiet hint of disappointment, as if they looked on Alonso like a good kid who had got in with the wrong crowd. Patronising, perhaps. Puritanical, certainly. After all, Madrid had stemmed the bleeding. Defeated 5-0 in November, now the score was 1-1. And better was to come. But, still, it was true.

Three days later, the feeling grew even more intense, this time turning bitter and angry. In an often fractious Copa del Rey final, in which the mutual affection appeared buried forever, in which Spanish national team-mates on both sides were locked in feuds all over the field, Xavi again racked up a huge number of passes: 135. Alonso completed just 35. But this time, it did not matter: Real Madrid won the Copa del Rey and might even have found a formula for beating Barcelona in Europe, too.

For Xabi that new formula meant a revolution in his role. Yet he embraced it. He had not failed; he had, rather, succeeded in playing a different role. The question is whether it is a role that will prosper over the next two meetings. A role in which Xabi was not like Xavi. This time telling them apart was easy. Xabi Alonso was the one holding the Cup.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion