The orthodoxy has it that the W-M formation was developed at Arsenal by Herbert Chapman in the early part of the 1925‑26 season in response to a heavy defeat at Newcastle. The orthodoxy, though, may not be correct.

The Football Association, worried by the increasing negativity of football and the widespread use of the offside trap, had changed the law in summer 1925, ruling that just two defensive players were required to play an opponent onside, rather than three as had been the case. The most obvious immediate effect of the change in the offside law was that, as forwards had more room in which to move, the game became stretched, and short passing began to give way to longer balls.

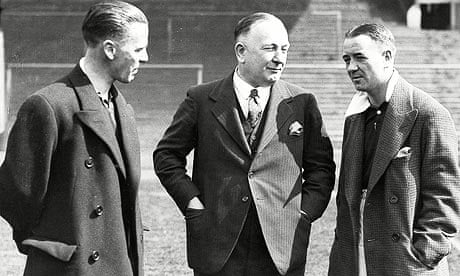

Some sides adapted better than others and the beginning of the 1925-26 season was marked by freakish results. Arsenal, in particular, in their first season under Chapman, seemed unable to settle into any pattern of consistency and after beating Leeds United 4-1 on 26 September they were hammered 7-0 by Newcastle United on 3 October.

Charlie Buchan, the inside-right and probably the team's biggest star having joined from Sunderland that summer, was furious, and told Chapman he was retiring and wanted to stay in the north-east. This Arsenal, he said, were a team without a plan, a team with no chance of winning anything. Buchan had argued from the beginning of the season that the change in the offside rule meant the centre-half had to take on a more defensive role, and it was notable that in Arsenal's defeat at St James' Park the Newcastle centre-half Charlie Spencer had stayed very deep. He had offered little in an attacking sense, but had repeatedly broken up Arsenal attacks almost before they had begun, allowing Newcastle to dominate possession and territory.

The deep-lying centre-half

The use of a deep-lying centre-half was not uncommon; Chapman himself had employed Tom Wilson in a spoiling role in the 1922 FA Cup final, in which his Huddersfield Town side beat Preston North End 1-0. Where they did break new ground – or at least where it has commonly been believed they broke new ground – was in recognising the knock-on effect this would have at the other end of the pitch.

Buchan argued, and Chapman agreed, that withdrawing the centre-half left a side short of personnel in midfield, and so proposed that he should drop back from his inside-right position, which would have created a very loose and slightly unbalanced 3-3-4. Chapman, not wishing to compromise Buchan's goalscoring aility, preferred to leave him high up the field, instead using Andy Neil in the withdrawn role. Over the next five seasons, though, an additional inside-forward did drop back, creating a 3-2-2-3 shape. In that system Arsenal won the FA Cup in 1930, and the league in 1931, 1933, 1934 and 1935 (although Chapman died midway through the 1933-34 season).

At least that's what we thought happened – what Chapman himself claimed happened – that a combination of Buchan and Chapman's analytical brains came to a radical conclusion about how space could best be manipulated under the new offside law and revolutionised football as a result. A couple of weeks ago, though, I received an email from Dave Juson who, while researching a piece on the 1925-26 season, had come upon an extraordinary column written in the Southampton Football Echo.

New information

On 3 October 1925 – that is, on the day of Arsenal's revelatory defeat at Newcastle – "Cherry Blossom" wrote under the heading "the W Formation" that "the Saints were beaten by Bradford City at the Dell on Saturday [that is, 26 September] by tactics. The home team, to my mind, had more of the play than the City, and put up the better exhibition of football, that is, as the game was played before the offside law was altered. But the City were very smart indeed on the ball, and their tactics did the rest, so that they scored two goals, while the Saints could reply only once.

"There is a lot of talk in the dressing rooms at the moment over what is known as the W formation in attack to deal with the changed conditions of play. In this formation the centre-forward and the two extreme wingers go well up the field – staying only a yard or so onside – and the two inside wing-forwards remain behind, acting as five-eighths, or in others words operating in a sphere of play near the half-backs and behind the three advanced forwards."

It would be startling enough if Cherry Blossom were talking about the Bradford manager David Menzies as a lone tactical maverick – intriguingly, suggesting Bradford's directors were aware of the tactical possibilities of the game, at the end of the season Menzies was replaced by Colin Veitch, who as a player at Newcastle had a reputation as a tactical mastermind; for his influence over the 1910 FA Cup final against Barnsley, see Alex Jackson's article in the next issue of The Blizzard. But Cherry Blossom implies that use of the W-system was widespread.

"The goalscoring figures up to date go to suggest that this is the method mostly adopted, for there have been scarcely any cases of the inside wing-forwards running riot in the goalscoring sense, while on the other hand, five, four and three goals in a match have been credited the centre-forwards with startling frequency, and the extreme wing men have also figured largely in the goal-scoring department."

The withdrawn inside-forward

Chelsea, then, like Southampton, a Second Division side, had been one of the major beneficiaries of the new rule, the ageing Scotland international Andy Wilson revelling in the withdrawn inside-forward role in which his declining pace was less of an issue than it had been when playing higher up the field the previous season.

What's fascinating about the withdrawal of the inside-forwards is that it seems to have happened almost independently of changes at the other end of the pitch, or at least not as a consequence of them. "With this disposition of the attack," Cherry Blossom went on, "the inside wing-forwards help, when their side is on the defensive, as additional half-backs, and practically throughout the game the centre-half-back becomes a third back."

The way Chapman and those, like Willy Meisl, who credit him as the progenitor of W-M, tell it, the inside-forwards retreated in the late 20s to fill the space left by the retreat of the centre-half to become a third-back. That, frankly, always seemed a little odd, given that in central Europe and South America, the inside-forwards began the process of dropping off long before the centre-half took on a defensive role.

Other than tradition, there seemed no reason why a similar process should not have occurred in England; it appears now that it did – even if it took the change in the offside law to prompt it. Cherry Blossom makes it sound as though the retreat of the centre-half occurred almost independently of the changes in the forward line.

Southampton use the W-formation

Cherry Blossom urged Southampton to adopt the W-formation against Port Vale that afternoon. They did so, and achieved a creditable away draw, and then used it again in beating Darlington 4-1 at home on the Monday. Cherry Blossom's column the following Saturday – that is, a week after Southampton's draw at Port Vale and Arsenal's defeat at Newcastle – highlighted Dave Morris of Raith Rovers as the model of the modern deep-lying centre-half.

"He positions himself," Cherry Blossom wrote, "a little in front of the backs and midway between them, whilst the wing half-backs look after the opposing wing-forwards, leaving the backs and the centre-half-back to deal with the three inside-forwards of the opposition [the terminology here is a little confusing – he means the centre-forward and what later became known as the two inside-forwards]. In this formation the inside-forwards work closer to the centre-half-back than formerly, and the pivot feeds these two, who in turn open the attack where they see an opportunity."

What's remarkable is how rapidly the W-formation seems to have spread, particularly given the absence of television footage. If teams as diverse as Southampton and Raith were using it by early October, it seems to have been a nationwide phenomenon within seven or eight games of the new season. The offside law was clearly the spur, but given the occasional use of the third-back by an array of teams before 1925 and the way the forward line had evolved elsewhere, you wonder whether 2-3-5 might have become W-M even without the change. Either way, what is clear is that, although Chapman's Arsenal were by the end of the decade the finest exponents of the new system, they were not the first team to use it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion