The historian

John Fennelly, club historian

According to legend, the cockerel and ball that sits on top of the East Stand, having been relocated from the West Stand in 1958, was full of gold. I don’t know how it got started but one bloke was sufficiently convinced to climb up and try to steal it. He was arrested. That would have been in the 1940s or 1950s.

By the 1980s, the Tottenham chairman, Irving Scholar, decided to see for himself. The original copper piece was cast by William James Scott, who had played for the club in the old amateur days, and it went up in 1909. I was a reporter on the local paper when Scholar got it down and opened it up. There were a couple of photographers with us and we smiled when we saw what was inside – a soaking wet, old handbook.

It’s amazing how these sort of things gather momentum but it is the little stories about White Hart Lane that I love. Each one of them adds a layer of character to the place. When I first started working on the local paper, I used to interview the old members of staff, who had been at the club since before the second world war. They used to tell me about an old boy who was employed to walk down the tunnel and bang two bin‑lids together to drive away the pigeons.

There was also a thing about people bringing cockerels to the matches – in the 1960s, I think – because the cockerel was on the club’s badge. They’d just let them go. Can you imagine that these days? There was an old geezer on the ground staff, who was an animal lover, and he would round up the cockerels and take them home. At dawn every day, these bloody things would be crowing away and the club would get hammered with complaints from the neighbours.

During the first world war, the ministry of war took over the stadium and the East Stand was used as a factory to make gas masks, gunnery and protection equipment, while in world war two the stand was a morgue because the blitz happened round here. Football carried on during that war and the club would have games stopped when a doodlebug went across. They’d wait until it had gone and you’d hear it explode somewhere else and then they’d carry on. It was incredible.

In the second world war, the idea was to keep things as normal as possible on the home front. Wherever soldiers were based, they could guest for the nearest club. Our teams during the war had hardly any Spurs players in them and the club might even make an announcement to the fans – “Can anyone fill in at left-back?”

People used to say that there were ghosts at the stadium. I don’t believe in all of that but so many people tell you about them. One evening, I remember sitting in the office at the Red House on the High Road – where the club had started – and something collapsed behind me. It sounded like the whole ceiling had come down but, when I turned round, there was nothing there. I’ve seen doors open, seemingly, by themselves. It’s strange.

My first game at White Hart Lane was in 1966. My dad took me and we lost to Burnley. We watched it from The Shelf, which was the most famous part of the ground. It was so unusual to have a terrace at a second level running along one of the sides, rather than behind a goal.

I remember our FA Youth Cup final against Coventry City in 1969-70. The two legs finished level on aggregate and so it went to a replay, which was drawn. We won the second replay 1-0. Graeme Souness played for us and he didn’t get a medal because he had been sent off in the first match. They let him play and then didn’t give him a medal. How offensive was that?

After that, I’ll never forget our win over the league champions, Leeds United, in 1975, which we needed to avoid relegation. It was the game in which Alfie Conn sat on the ball and upset both sides. Incredibly, I missed the 1984 Uefa Cup final win over Anderlecht because I was on holiday but I was there in 1972 when we won the same trophy against Wolverhampton Wanderers. As with Anderlecht, the second leg was at the Lane, which made it even more special.

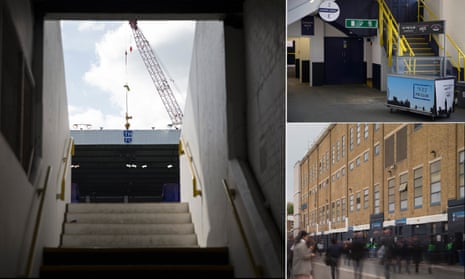

It is amazing to think how much has changed since the club was formed in 1882 and they played on Tottenham Marshes and Northumberland Park before the move to White Hart Lane in 1899. But what is great for me about the new stadium being built on the existing site is that it remains the proverbial goal-kick from where it all started.

The legend

Cliff Jones, 1961 double winner

I will never forget the look on the faces of the Gornik Zabrze players. They were looking around and saying: “What on earth is this?” They were intimidated and you could say that they were a goal down before we kicked off. It was the first ever European Cup tie at White Hart Lane – in 1961 – and we absolutely slaughtered them. It finished 8-1 and it was down to the crowd. They just picked us up and said: “Go.” When you played on the continent, you had running tracks around the playing areas and so the spectators would be 15-20 yards back. But at White Hart Lane they were right, smack on top of you.

The tunnel, in those days, was at the bottom end of the ground and we would come up and out of it. When we did, we’d see the East Stand, which was always chock-a-block, and it was just the roar that went up and the sense of expectation. I always used to walk out behind John White – that was my superstition. They were special times, particularly the European nights.

Gornik had beaten us 4-2 in the first leg over in Poland and they were a very good side. Most of them were in the Polish national team. But Bill Nicholson got us right up for the second leg and that night I think we would have beaten any team that had ever been or ever will be. Above any game I played at White Hart Lane, I remember that one.

It was the beginning of the glory, glory European nights and no team wanted to draw us, partly because of the atmosphere that our crowd would generate. We beat everyone at White Hart Lane, even Eusébio’s Benfica, although they got past us on aggregate. Eusébio didn’t get a kick in either leg but he did have Dave Mackay marking him. Mackay was quite intimidating. We’d wear all-white strips in Europe and there was just something about those evening kick-offs. The air seemed a bit fresher and it was as though you could run a bit longer and a bit faster.

When I first arrived at Tottenham, they used to have a marching band providing pre-match entertainment. They would march on the pitch and the bloke at the front would throw his baton up into the air. Every now and then there would be a big roar and you’d know he’d dropped the baton. It was totally different to what it is now.

I almost did not make the FA Cup quarter-final replay against Sunderland in our Double-winning year. I used to come down to White Hart Lane with my wife, Joan, and a good friend of mine, and we could only get as far as Creighton Road because everything was gridlocked. Creighton Road was the one where Bill Nicholson lived and it was about a mile from the stadium. So, I had to make my way on foot. I got to the gates at White Hart Lane and it was surrounded by supporters, thousands and thousands of them. I tried to squeeze through.

I said: “I’m playing tonight.” People said: “What are you talking about, mate? Ah, Cliff. On you go!” They pushed me through and I got in 20 minutes before kick-off. A number of the lads experienced the same thing but we still won 5-0.

When you talk about Spurs and White Hart Lane, you talk about Bill Nicholson. On the field, we had three players – Danny Blanchflower, Dave Mackay and John White – but the main man was Bill Nicholson. He ran the club from the bootroom to the boardroom. You didn’t mess with him. He had an office at White Hart Lane and you didn’t want to be called into it.

One time, Jimmy Greaves convinced me that I should go in to see Bill about a pay rise. It didn’t go very well. I told him that I deserved it because I thought I was the best winger in Europe. “Is that right, son,” Bill said. “On the way out, close the door behind you.” And that was it. I must say, though, that some months later, he called me in and he did give me the rise. That was his way of doing things.

It will be emotional to see the old stadium knocked down but I think the ghosts will continue to lurk around. I’m sure Blanchflower will be there somewhere. And Mackay.

The fan

Paul Bateman, conductor, composer

I started going to White Hart Lane with my dad in the 1960s and, in those days, the ground was all about the crush barriers. We used to get to the matches so early – two hours beforehand was considered late – and the idea was to get near to a barrier. My dad would sit me on one. We’d have brought our lunch along and we’d eat it there.

I have a vague memory of a children’s price of a shilling, which is now five pence, and if you wanted to go into the enclosure, which was the narrow strip along the West Stand, it would be another shilling. I think the enclosure was a little bit safer for families.

I’d usually be in one of the ends, squashed together with everybody and going forward when there was a goal. It was dangerous but there was more of a unity between the fans. You learned to anticipate the surge and it was always best to get down to the front, although even that was dangerous because people were falling towards you. Fans used to jump up into the air and almost get on to the side of the pitch.

The sights and sounds and smells made such an impression on me. As you came into the ground, you could buy a tea or a coffee or get burgers, hot dogs and chips, so all of these aromas would be swirling around. There would also be a man selling goal-time tickets, which was a sort of raffle. He used to shout: “Get your goal-time tickets ’ere. Eighty-five pound in prizes.” That was a lot of money back then. It is much more formal now because the seats, obviously, had to come in.

The stadium looked completely different when I first got hooked on the Double-winning team. The cockerel and ball has stood the test of time but The Shelf has not. That was more of a separate thing in those days. The corners of the stadium were also not filled in with seating. It was just four standalone stands.

I can still reel off the famous team – Brown, Baker, Henry, Blanchflower, Norman, Mackay, Jones, White, Smith, Greaves, Dyson. They were up on my bedroom wall. They were such characters and Dave Mackay was an incredible character. He was the hard man of the team. Years later, when I was the organist at the Palmers Green United Reformed Church, I played at the wedding of one of Cliff Jones’s children. I remember very clearly seeing him there, walking around.

You cannot make direct comparisons to today’s team because the fitness levels are different but the 1960s team had that skill level. I think it started in the 1950s when Arthur Rowe had his push-and-run team, which won the league in 1951. Bill Nicholson was a member of that team so he had a way of playing. The great teams just know where each other are on the pitch and they have personalities that click.

My strongest memories of matches are from longer ago. I am reminded of certain games, like when we beat Crewe Alexandra 13-2 in the FA Cup in 1960. Crewe were a lowly team, so it was jolly good of them to get two goals. That result remains the club’s record win. I remember being in massive crowds for league fixtures against Manchester United and Everton and I came to some of the early European ties.

There was also an unusual one – a charity match between the FA Cup-winning teams of 1991 and 1981, with the likes of Glenn Hoddle and others. The 1991 team were considerably fitter but there was, quite clearly, more skill in the 1981 team. It finished in a 2-2 draw.

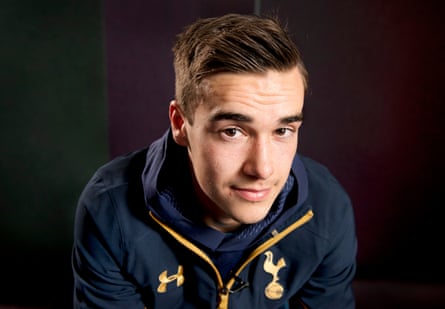

The player

Harry Winks, midfielder

One of the things that would probably surprise people about the stadium is how low the ceiling is in the home dressing room. I can almost touch it. It’s quite tight in there and it gets the camaraderie going between us, especially when we put the music on before matches. We feel we’re all together and part of the team, as opposed to having a big dressing room where everyone is scattered all over the place. I’d say it’s old-school, but with a modern touch.

My dad is a massive Spurs fan who started going to White Hart Lane with his uncle when he was knee-high, and I’ve grown up with the club in my blood. I can’t really describe the feeling when I’m in the tunnel, about to walk out and they play the music. I think it’s from Star Wars. I get hairs on my neck, like me and my dad did when we used to go as fans in the crowd. It’s just amazing.

My favourite game as a fan was probably the first one that my dad took me to – against Middlesbrough, when I was six or seven. I’d started playing at the club’s academy and one of the coaching staff managed to sort us out with tickets in one of the directors’ boxes. We were bang on halfway, in the leather seats. I remember the crowd and my little ears being overwhelmed by the noise. When I play now and I hear the crowd, it still gives me the buzz I had when I was that age.

Every European night that I’ve been to or been involved in, whether it’s Europa League or Champions League, has been special. I didn’t go to the Inter Milan game in 2010-11, when Gareth Bale ran Maicon ragged, but I remember going to the Real Madrid quarter-final tie later in that Champions League season. I was a flag bearer on the night so I got to go on to the pitch before the game. I was up close with Cristiano Ronaldo – I could see him up close. All the academy players got to do flag bearing once or twice a season in the European games and I was designated Real Madrid. I was really lucky.

I made my full Premier League debut at White Hart Lane in November of this season against West Ham and it was pretty surreal when I scored. I ran over to the manager and my mum and dad were in the box just above the dugout and I remember looking up to them and blowing them a kiss. It was a crazy game, with us winning 3-2 thanks to Harry Kane’s two late goals, and it was just a crazy day overall. A few of my mates are diehard West Ham fans and I got a text off one of them, saying: “I can’t believe you’ve done that.”

One of my earliest memories of White Hart Lane was training there when I was six or seven on an indoor ballcourt that was on the side of the stadium. It was astroturf – for 10 v 10 – and there was a little window upstairs where the parents could sit and watch. There were quite a few times when I would finish training and see some of the first-team lads. I remember meeting Jamie Redknapp and Fredi Kanouté. I trained there twice a week after school until I was eight or nine. Unfortunately, it got knocked down and we moved to Chigwell to train as I got older.

Everyone will be emotional and sad when White Hart Lane is knocked down because of the prestige and heritage of the place. But at the same time, there is excitement about the new ground. Many more fans will be able to come to games and, hopefully, the atmosphere will be as good. Everyone is just really looking forward to it.

The White Hart Lane finale will benefit the Tottenham Tribute Trust, the club’s charity for its former players who are in situations that compromise their quality of life. Visit www.tottenhamtt.org