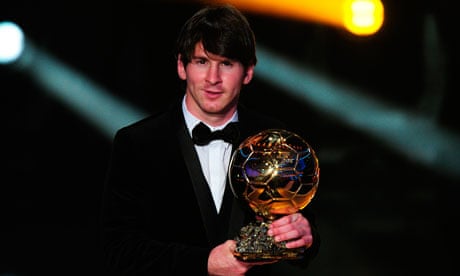

Leo Messi was wearing a dickie bow last night. Proof, some said with a smile, that he knew he was going to be awarded with a second successive Ballon d'Or – after all, Xavi Hernández and Andrés Iniesta were only in ties. But he didn't know: amid all the shock, the disgust and the pathetic patriotic paranoia, the man most surprised at Messi's award was Messi. On his way into the gala, he was asked whether it felt a bit strange to be the best player in the world and yet still know that he wasn't going to get the award for the world's best player. Messi mumbled something along the lines of: no, not really – Xavi and Iniesta won the World Cup.

And there in a barely audible phrase was the crux of the issue. This is the first time since 1974 that in a World Cup year when it was won by a European team the winner has not been from the world champions. And in 1974 it was Johan Cruyff – the World Cup's moral winner. Only one Spanish player has ever won the award – Luis Suárez in 1960 – and for years the reason was assumed to be that, while Madrid and Barcelona had been among the continent's very best teams, there was no international success to push Spanish players over the line. Now at last there is. But this time, more than any other time, the World Cup has not been decisive. If it had been, Messi would not have won the award.

Messi was extraordinary in 2010. If the Ballon d'Or is given to the player who played the best football over the course of the year, he is a worthy winner. It was the year in which there was no doubt. Fans spent much of it scraping their jaws off the floor as he performed with barely plausible brilliance week after week. Even the sceptics were won over. The hammering of Arsenal, especially, turned heads . He became the complete player. The debate surrounding him was elevated to a different plane. It was no longer enough to ask whether he was the best now: was he, in fact, one of the best players ever?

He produced more dribbles, more goals and more assists than anyone else in La Liga and was the Champions League's top scorer. He was the European Golden Boot. He scored 60 goals in 59 games. Despite arguments to the contrary, he played rather well in South Africa. But that basic construction – best player gets vote – has rarely been followed before. This is not the world's best player award. It is the year's greatest achiever award. On the greatest stage, Messi did not leave a lasting mark. And that point strengthens the case of the two men who shared the podium with him last night: without Xavi and Iniesta, Messi was not as good; without him, they were. Without him, they won the World Cup.

Ultimately, the decision rests of the criteria employed. Trouble is, how do you apply a criteria with the electorate expanding as it has? In 2006, 56 people voted, in 2010 96, this year 427. Next year it will be 624. Officially, the Ballon d'Or "awards the best in their category, without distinction of championship or nationality for their achievements during the year". Voters are reminded to be impartial and to take into account all criteria. It is awarded for "on field behaviour and overall behaviour on and off the pitch". Voters were reminded of the importance of "individual" achievements and "team (trophies)".

If it was down to trophies, a basic count, then one man stands above the rest: Wesley Sneijder was the key creative spark of the Internazionale team that won the treble and helped carry Holland to the World Cup final, scoring five times en route. (By the same criteria, the omission of Diego Milito even from the shortlist is baffling but for pointing to the significance of South Africa: he scored the goal that clinched the title, the goal that won the Italian Cup and the goal that won the European Cup but was irrelevant to Argentina. The fact that Arjen Robben has hardly been mentioned jars a little too: Bayern Munich's most important player by miles, he won a league and cup double and reached World and European cup finals).

Under the old format, it would have been Sneijder. The Ballon d'Or used to be voted on by the correspondents of France Football but the award has been hijacked by Fifa – frustrated at its inability to sink the Ballon d'Or with the Fifa World Player Award – and now it is an amalgamation of both trophies. Now, international coaches and captains also get a vote. Counting only the France Football votes, Sneijder would have won. Messi would have been fourth. It is the coaches and the captains not the correspondents who have given him this award.

But when it comes to trophies, none weigh so heavily as the World Cup. Precedent, if not written rules, has pointed that way. Ronaldo in 2002, Cannavaro in 2006. And although Sneijder's case there is strong too, he did not win the World Cup. Here, no one can match Spain.

Iniesta's winning goal – and, it should not be forgotten, his wonderful tournament – propelled him into the top three, despite a year in which he had suffered with injury at club level. Many were furious when José Mourinho insisted that Iniesta did not deserve the award, claiming that "any player could have scored the winner in the final", but he had a point. In Spain, there was talk of Iker Casillas because of his vital intervention against Paraguay in the quarter-final and Holland in the final (his club season had been surprisingly poor). There was not, strangely, much talk of David Villa: another international top scorer award seemed counter-balanced by not having played for Madrid or Barcelona before the tournament.

And then there was Xavi. If football is about legacy, about impact and importance, Xavi's claim seemed unassailable. If it takes into account the whole of 2010 and not just the back of 2009-10 and the World Cup, it grows stronger yet: has any game stood out like this season's clásico in which Xavi led his side to an incredible win? In the past three years, Xavi has won it all. A European Championship in 2008, six trophies out of six with Barcelona (league, Copa del Rey, Champions League, World Club Cup, Spanish Super Cup, European Super Cup) in 2009, and the World Cup in 2010.

Not just won them: won them in style. There is an argument that suggests, especially after the stunning 5-0 destruction of Real Madrid, that this Barcelona team might be the best club side there has ever been. By winning back-to-back European and world championships, much the same could be said about Spain – they were unusually worthy winners of the World Cup. But it is not just that those two teams have won it all; it is the way they have won. Rarely has a team had such clarity of style, such a distinct identity, as Spain and Barcelona. An identity in which they dominate, control and anaesthetise the opposition, picking apart their defences, undoing their armour piece by piece.

That style is Xavi's style. Xavi lays for Barcelona and Spain. Really plays for them; he is not just in the side, he does not just play, he makes them play. It is not just that he is a great player, which he is, but that he makes other players great. He is the ideologue behind two of the best teams there has been. If any player has marked the last three years, it is he. At 31, he probably won't get another chance to win the award – God knows how many Messi might win – and he should have won it this year. For this year and the previous three; for this era. His era. No matter what the Daily Mail thinks. Especially because of what the Daily Mail thinks.

And yet one thing the criteria is clear about is that this is an award for 2010 alone. In the past, France Football has talked too of "trajectory"; this year, that has not been the case. That's one explanation. In the scramble to explain last night's surprise there have been plenty of theories forwarded. The most tragically predictable has been proffered by the newspaper Marca whose cover ran on a photo of Mourinho (about whose award there has been rather less anger, even though he got the nod ahead of Vicente del Bosque) and Messi. In the middle was a small picture of Sepp Blatter. The headline read: "Two Giants and One Anti-Spaniard". The paper's name was written in red and yellow. "This," complained the cover, "is the flag the president of Fifa hates."

But Blatter did not vote. Journalists, coaches, and players did. And they voted for Spaniards in huge numbers: 42% of the first choice votes went to Spaniards. For the first time ever, seven players from the same country picked up at least one first choice vote. That hardly smells of conspiracy. More skewed surely is the desire for someone, anyone to win the award – just so long as they are a Spaniard. And, in fact, Spain – and here it's worth reminding many in this country that there was no candidate called Spain – may have been a victim of its own success, its very nature. Of the fact that its collective nature meant there was not one, single stand-out candidate for everyone to get behind. The vote was split: Messi won with 22.65%, Iniesta had 17.47% and Xavi 16.48%.

The fact that there is an open vote has allowed some to snipe at who chooses the winner, and pick out those "guilty" for this "crime". But before everyone starts patronisingly laughing at the stupidity of votes from those third-worlders who don't know anything, check out last year's most idiotic voter Besides, that did not damage Spain, either: plenty of votes came in from countries that were being dismissed as irrelevant last night. Although banned from voting for international team-mates, players do indeed – as the example above shows – sometimes vote politically. Amid almost 500 votes, though, that hardly seems sufficient to tip the balance. The wrong player might have won, but no one was actually wronged.

Last night, Leo Messi was surprised. He was not the only one. In 2010, the Argentinian eclipsed everyone. But even he didn't expect that to include his World Cup winning team-mates.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion